Stories from Poland

Anna Turula teaches at the School of English at the University of Wroclaw in Poland and we are welcoming her back for her second interview for our Blog! She previously worked at the Pedagogical University in Krakow.

Despite changing institutions, Anna remains a committed virtual exchange enthusiast. In her previous conversation with UNICollaboration, she mentioned her research when talking about the role of CLIL and its role in virtual exchanges. (CLIL, which stands for Content and Language Integrated Learning, is an educational approach where a non-language subject, like math or science, is taught in a foreign or second language.)

Anna Turula teaches at the School of English at the University of Wroclaw in Poland and we are welcoming her back for her second interview for our Blog! She previously worked at the Pedagogical University in Krakow.

Despite changing institutions, Anna remains a committed virtual exchange enthusiast. In her previous conversation with UNICollaboration, she mentioned her research when talking about the role of CLIL and its role in virtual exchanges. (CLIL, which stands for Content and Language Integrated Learning, is an educational approach where a non-language subject, like math or science, is taught in a foreign or second language.)

Anna explains how adopting the CLIL approach is the way a virtual exchange can become a ‘critical’ virtual exchange when the critical or civic element becomes the content.

“For a critical focus, it’s the content that you need to concentrate on. I’ve been delving deeper into the outcomes of the study where I interviewed 40 teachers who were integrating VE into their own teaching. Twenty were university teachers and 20 were school teachers involved in e-twinning programmes.”

Anna says that her initial intuition has proved correct, and that it’s content integration that helps make the virtual exchange ‘critical’.

Similarities and Differences in VE approach

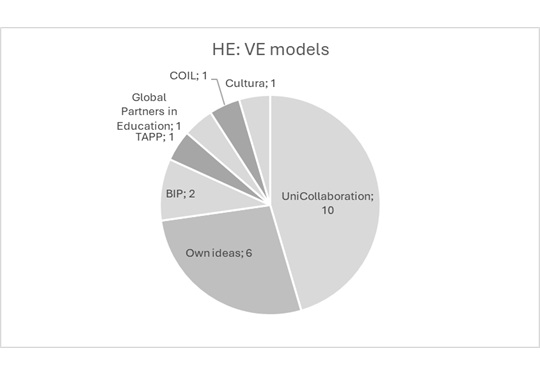

“There are definitely more similarities than differences between the two modes’, explains Anna, ‘Of course, at the university level, there are a variety of modes, like BIPs, (blended intensive programmes) and UNICollaboration, and COIL.There’s also TAPP (the Transatlantic and Pacific Project) and Global Partners in Education.”

Regardless of the model, in Poland, Anna discovered that teachers adopting any of the university modes as well as e-twinning all concur that virtual exchange is transformative.

“Teachers believe that virtual exchange has transformative power -that it makes the students better human beings. Perhaps this is the critical element of the exchange? And it also makes teachers better teachers.”

By this, Anna explains that teachers become more creative and think outside the box. And this she found to be true for teachers at secondary level and at university level.

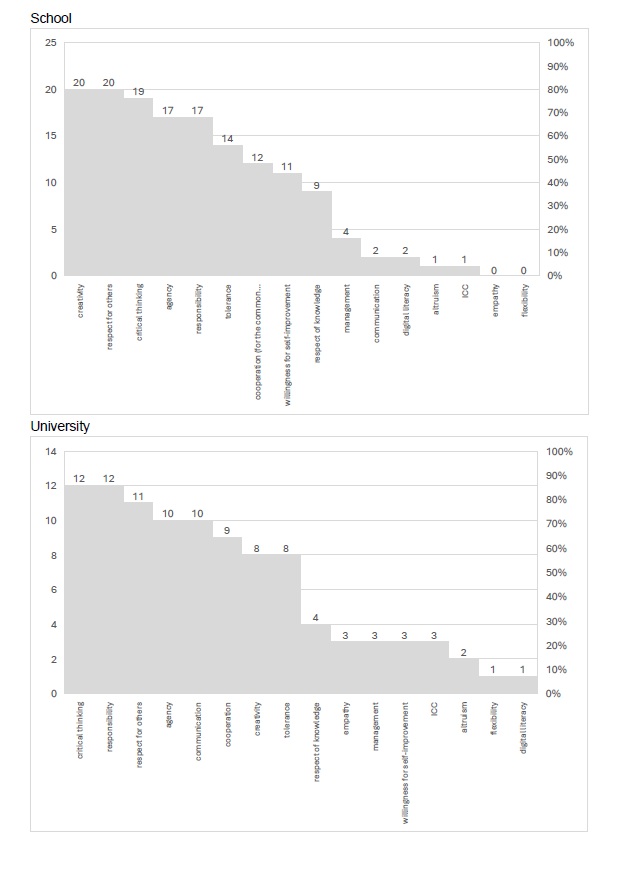

“The university teachers and the school teachers mentioned virtual exchange and its role in developing the 21st century competences and in developing digital citizenship and citizenship in general.”

One significant difference

“University teachers are more free and easy about what they do”, says Anna. “Their approach is less prescriptive as they have fewer constraints than school teachers. School teachers, on the other hand, have more boxes to tick and more constraints on what they can and can’t do.”

Anna thinks there are advantages to being part of the system, because there are certain requirements you must cover.

Important concepts such as digital citizenship are more frequently included in the school exchange as opposed to the university exchange.

“It’s because the system requires that, and the teachers get rewarded in different ways for doing that. There is a kind of competition, at least in Poland. For the best exchange, there are certain tick-off elements. And the teachers try to follow those elements.

Whereas, when you are freer, you probably follow your own intuitions more than certain recommendations. This difference made me think about the advantages of having a system with a list of requirements and having competitions to highlight the best exchange, for example.”

On the other hand, says Anna, if you cover certain things only because you want to satisfy the system, perhaps the extrinsic motivation for carrying out the exchange may be a little weaker. Or of a lesser kind?

“So, this was my reflection based on the results, that the school teachers have more ideas, there is more digital citizenship, there is even more critical virtual exchange.

There is action, social and civic action taken out of the classroom and this is valuable. Perhaps this is where we could follow as university teachers.

But at the same time, motivation is also an important factor, and what kind of motivation is behind the choices.”

Systems and templates

When undertaking her interviews, Anna asked whether the teams were international teams working collaboratively or whether there is only cooperation with people working separately in national teams and putting the results together at the end of the project.

For the most part, the school teachers confirmed the teams were collaborative and international because this was the requirement and constitutes best practice for e-twinning and they wanted to follow such requirements.

Importantly, school exchanges are also predominantly cross-curricular. At university level, Anna found out that these aspects were less frequent.

“When you work for school, you meet other teachers in the teacher’s room. And it’s easier to form an interdisciplinary team, and to make the exchange cross-curricular.

At the university level, you probably work for a department where people have similar interests and it’s much more difficult to make the exchange cross-curricular because you don’t reach out to other departments very much..

So, in this case, again, there is a section of virtual exchange at the university level, at least in Poland.

And it happens at the university language centres, where teachers have students from different departments. For them, reaching out and examining various types of content may be more practicable than in a language or literature department.”

Both sides stand to learn from each other

Anna says she’s learned enough from her research to justify making some changes in her future collaborations. She will continue focusing on digital citizenship as she considers this civic education very important for her exchanges. But she will change some things as well.

“As a result of my research, I thought about reaching out towards those dealing with civic education, and perhaps sociology departments and psychology departments or cultural studies to make my exchanges reach across disciplines, following the example of the school.”

Of course, says Anna, the learning goes both ways. She says university teachers are more focused on intercultural communicative competence and this is where schools may have something to learn..

“I think that we value that a lot, and the activities that we implement that are supposed to raise awareness and to build and strengthen intercultural communicative competence. Ours are more diverse and much more interesting than those carried out at school.”

Anna found that schools tend to focus more on etiquette, whereas universities make use of many other tools such as portfolios and reflection journals. That is perhaps what schools can take from university best practices as regards the quality of virtual exchange.